Making Peace With Bridges

A long-ago incident with bridges has recently resurfaced.

Many years ago, my then-husband and I went to New Orleans for the first time. We absolutely loved this city, home to great food, music, as well as scenic and architectural splendor.

But he always had a deeper zest for adventure than I did. Wherever we’d visit, he felt led to explore lesser-known places and spaces. Louisiana was no exception.

After we enjoyed a few days in New Orleans, he persuaded me to take the rental car through parts of the Louisiana countryside. He wanted a feel for the less touristy places in a hunt to unearth more of this magnificent state. I agreed, with a caveat: he had to do all the driving. I had just received my driver’s license at the ripe old age of 24 and was still nervous at the wheel.

So we drove on the winding River Road, which took us along the great Mississippi River. I was enjoying the ride – until we encountered the Huey P. Long Bridge, which goes over this river quite dramatically.

I have always gotten sick on amusement park rides – even kiddie rides. So I was horrified when we climbed the bridge’s steep incline and sped down the other side. Then we continued the quest to see more of Louisiana.

We finally returned to our hotel room late in the day, and I was overwhelmed by sheer exhaustion.

I had no idea the next day would be worse.

In the morning, my husband told me he wanted to get to the other side of Louisiana’s Lake Pontchartrain. We would drive on the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, which at nearly 24 miles long, happens to be the world’s longest continuous bridge over water. The causeway features two parallel two-lane highways, or spans, with the lake water visible even in between the spans.

This time, my husband thought it a good idea for me to hone my driving skills on the causeway, as it was straight with no inclines. So I began driving us across Lake Pontchartrain and soon realized this was a mistake.

For a long period of time all I saw was water, no land. Complicating matters, the bridge felt unsafe – without shoulders, so motorists couldn’t even pull aside. And where were the railings? One wrong move could cause the car to become a non-flotation device.

I panicked, barely able to breathe. My husband constantly tried to assure me that my driving skills could successfully and safely get us to the other side.

Once we reached the other side, I made him drive us back over Lake Pontchartrain and back to our hotel.

Only a few years ago, shoulders and improved railings were built on the causeway in order to help stranded motorists, as well as to prevent accidents and to keep vehicles from going into the lake.

By the time the causeway was strengthened, my marriage had long disintegrated for reasons other than the bridge fiascos.

A Tame Bridge

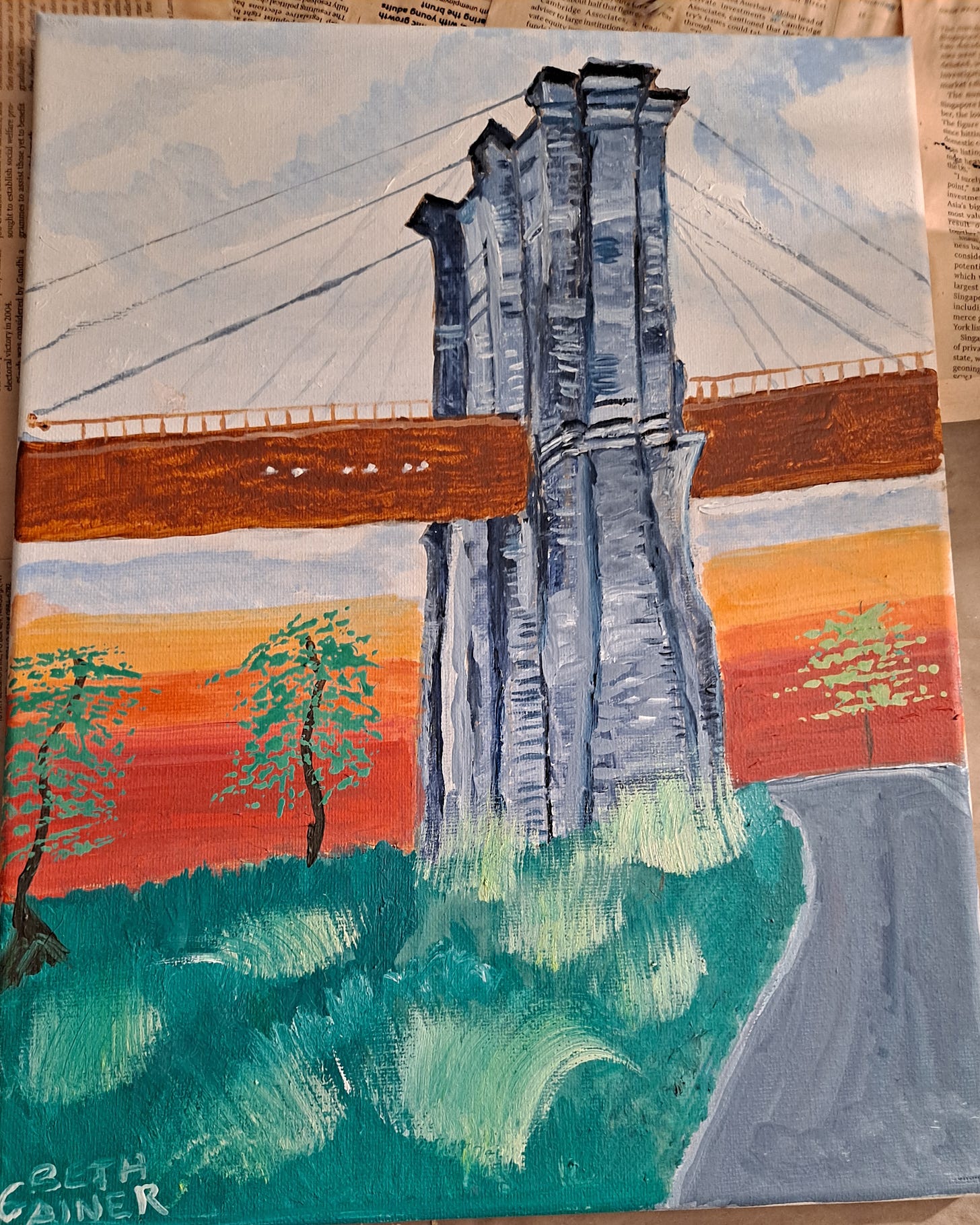

I am still understandably leery of bridges. So rather than drive on a bridge recently, I just finished painting one from the safety of my studio:

I cannot recall the name of the bridge I painted, but I know the structure is in my original hometown of New York City, which sports a plethora of beautiful suspension bridges.

I’m basically happy with how the painting, titled Bridging the Divide, turned out.

I generally feel uncomfortable painting architectural images, such as buildings, stonework, and bridges. But I felt good painting this bridge. And with all the chaos and divisions in the United States, I was disheartened and had to mechanically sit down at my art table and show up to the canvas. I am grateful that I did.

Bridges are powerful reminders of unity in spite of the divisions in the United States and the world at large. By creating this bridge, I feel like this message of unity comes through.

Love how your bridge painting turned out. I wasn't happy driving the 23 mile bridge over the Chesapeake bay bridge either.

Beth, the bridge memories are so vividly drawn, and the way you return to them through art — on your own terms carries a quiet strength that I always associate with you.